Quantum Computing Undermined by Radical Uncertainty: Part Two

Building systems that accommodate our biocomputers: acknowledging how humans actually think to cope with uncertainty in non-stationary problems

Clear your mind a second time (just as we did with the roulette wheel and President Kennedy in Part One). Imagine you are on your way to a first round job interview. The date is sometime in January 2020 and the location is London - you can choose where.In your mind, you will have an idea of how the next few hours will pan out: you will leave the house and you will make your way to the tube. You will arrive at the organisation’s office (or a good restaurant if you're lucky), wait for a few minutes after arriving and then meet your interviewers. You will then run through the initial pleasantries and start the main conversation. You have prepared well and have a body of experience behind you, and you are confident that you can deal with relevant questions asked of you. You’ll sip some coffee and then find out what you need to know from your interviewers - their goals and challenges. The conversation will then wind up and you'll take the same route as earlier to get home.Many things could have made those few hours run differently. The train may have been late or the questions you were asked could have been tricky or bizarre. You may have drawn swords with one of your interviewers. But the crucial thing to recognise is that you had a broad idea of what would happen and you imagined it as a sequence of events, processes, causes and effects.In fact, what you’d done is create a ‘narrative’ in your mind of what would happen. What you did not do, is sit at home for a week beforehand carefully working out the conditional, subjective probabilities that each event in the sequence would unfold as you imagined.

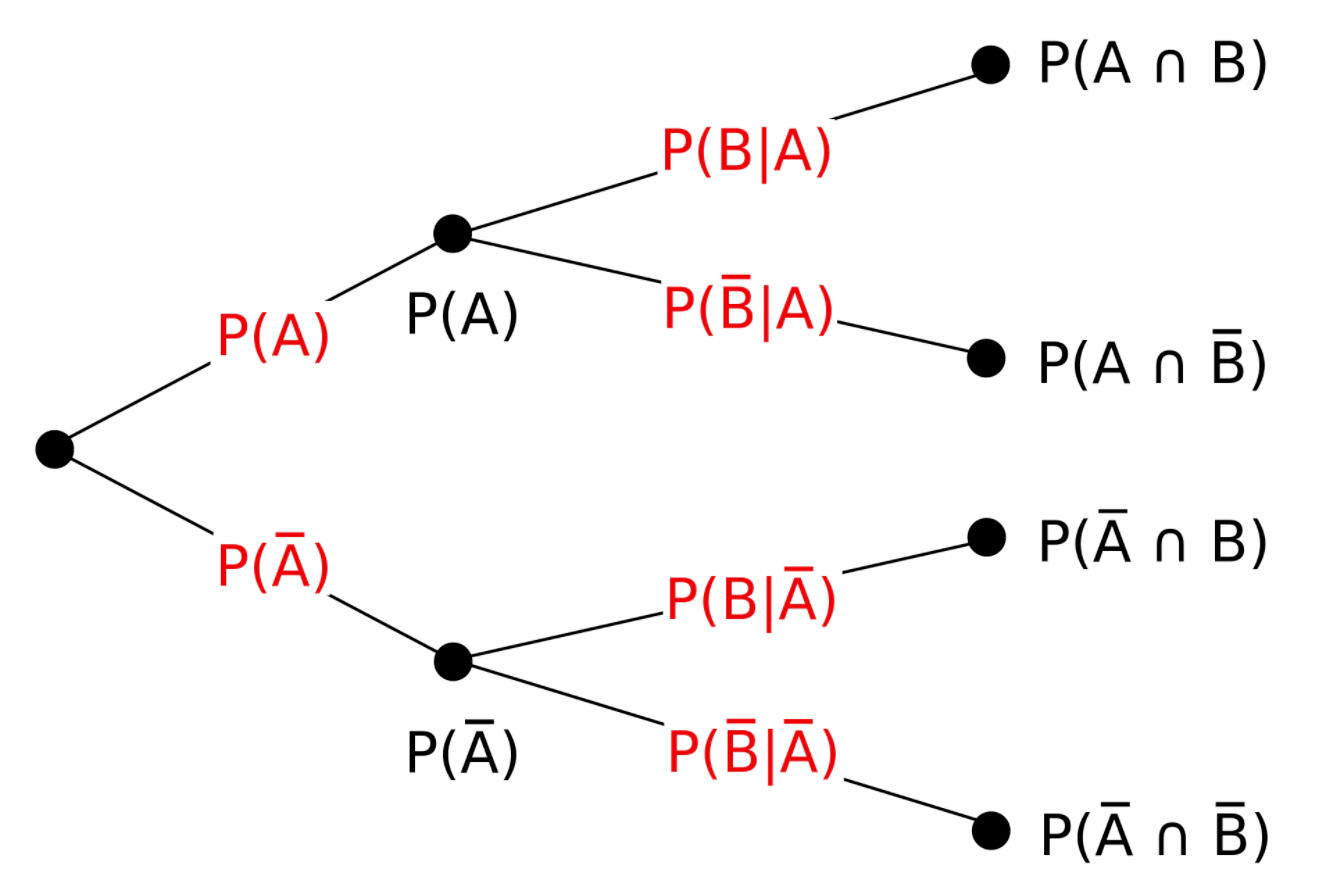

Did you imagine a narrative before leaving the house for the interview, or did you update your conditional probability tree?

This is because humans think and analyse the world in terms of stories or ‘narratives’. They help us make sense of our environments and the situations in which we find ourselves. They also help us make judgements about the future - both the immediate and the longer term, and they help us conceptualise cause and effect relationships. In fact, as noted economists John Kay and Mervyn King have explored recently (and as Keynes identified), narratives help us cope with uncertainty. They are what we use to deal with real-world, non-stationary problems.

This article is the second half of Rebbelith's exploration into how quantum computing is undermined by Radical Uncertainty.It will discuss why systems that help us cope with uncertainty must accommodate the way the world actually is, and the way humans actually think, so that we can make better decisions.

Read on below

Narratives and strategic business decisions

Just like our job interview, albeit on a more complex level, narratives are actually part of the process in which we approach normal business problems, such as whether to launch a new product or, indeed, a new venture. They constitute expectations about what we think the future will look like. They are a function of what is going on around us, our past experience and what other people think or do. They are central when people form business decisions. They are embedded in how an economy functions.As we saw in Part One, future asset prices or the success of a business are unpredictable. They are non-stationary problems and this means we cannot make reliable decisions based solely upon probabilistic reasoning. We all witnessed this in 2008.But as Mervyn King and John Kay have explored, this unpredictability does not stop us from making expectations and then acting - we do make business decisions in the face of uncertainty, and we do this by aggregating as much information as we can, and interpreting its meaning and relevance. We also gather information on what other people (such as customers, competitors or investors) are thinking and what they are doing - in effect, we try to identify their narratives of how things will look in the future. We then apply a causal model to this to imagine, as best we can, how these things will evolve. We construct a narrative. And we then act.

Macro forecasts and narrative importance

On the macro level, narratives are just as prominent and just as important. The task of understanding which are guiding a whole population would at first appear enormous, but examples of the most famous economic predictions have been founded on an appreciation of judgement using narratives.After the First World War, Keynes was among a few people who thought Germany would develop a sense of embedded anger over the reparations payments forced on them by the victorious powers. But, crucially, the economist linked this idea to what he saw as economic reality, and how he thought the German people would interpret reparations given their living conditions, and their wartime experiences. He thus predicted a potential future conflict:

“If we aim deliberately at the impoverishment of Central Europe, vengeance, I dare predict, will not limp. Nothing can delay for very long that final civil war between the forces of reaction and the despairing convulsions of revolution, before which the horrors of the late German war will fade into nothing, and which will destroy, whoever is victor, the civilization and the progress of our generation.”

The Treaty of Versailles: signing of the German Peace Treaty to negotiate post World War I conditions.

Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller observed that, here, “Keynes was not talking about pure economics as we understand it today. His words “vengeance” and “despairing convulsions of revolution” suggest narratives… reaching to the deeper meaning of our activities.”

This suggests that systems which can help us cope with uncertainty in non-stationary problems, like business decisions or economic forecasts, must acknowledge the importance of narratives.But finding tools to reveal the narratives surrounding our goals, predictions and aspirations has until now proven tricky.

Insights from an overlooked profession

One discipline has had to appreciate and attempt to understand the role of narratives to carry out its task. In fact, it is founded on its ability to do so and its work holds significant lessons for business and for economics.Public relations in its proper form, is broadly the discipline of translating the goals of an organisation or campaign to its publics in order to gain their acceptance. In essence, its task is to integrate those goals with a target audience. This is not just press agentry. The importance of this discipline cannot be ignored, and any organisation that does ignore its publics will fail.This task is complex and it is riddled with uncertainty: how will our publics react to the organisation’s goals? How do we reach those publics? How do we gain their approval for the organisation's goals and how do we know if we’ve been successful?The answers to these questions lie in locating and understanding the narratives that will either impede or support our goals, and this allows us to understand prevailing beliefs. Proper public relations has long used analogue processes to identify these narratives or beliefs, and build strategies that accommodate them.We will see that it is this discipline - narrative navigation - in collaboration with technology, that presents a solution to coping with uncertainty in many complex, non-stationary problems. The solution is not, as Standard Chartered seems to think, contained in the outputs of AI machine learning tools trained on vast synthetic datasets created by quantum computers.

Animal spirits and narrative networks

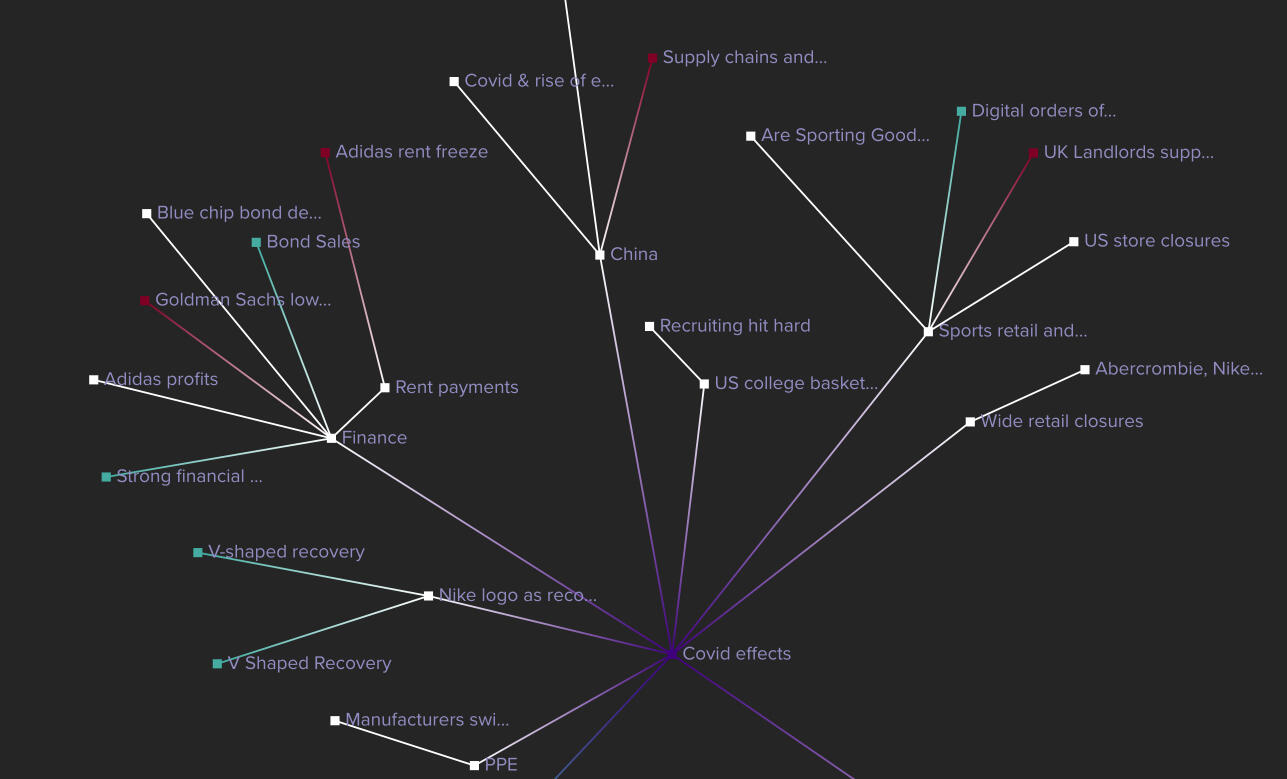

Belief is embedded in business. It is embedded in finance and markets. Keynes identified beliefs as crucial in describing how people make financial decisions, including buying and selling securities, under conditions of uncertainty. Belief is not, however, embedded in the processes that dictate how proteins fold. Nor does it affect the rules of the roulette wheel we were stood next to with Frank Sinatra in Part One.Robert Shiller has written about the importance of identifying and understanding prevailing narratives in making better economic and business decisions. It follows that if we can see what narratives are connected to our goals, we can form better strategies - especially if we can see not just what those narratives are, but also how they change and how other people respond to them.The problem has been identifying them and understanding them intuitively and quickly enough, and presenting the information in such a way that a human can make a sound decision. If this is achieved, we can create a plan for success that minimises uncertainty by understanding the narratives around us.What we require is a way of revealing and mapping the networks of narratives that affect our projects. We can then compare this map to our goals to understand where misalignments occur. This allows us to visualise where our goals may be at risk, or where, actually, there is opportunity. Simply, we can see where our own organisation’s or project’s narrative - the chain of events we hope to happen - may not be compatible with those around us.

Primary network map of the external narratives surrounding coronavirus that affected Nike from February to mid May this year.

If this approach, rather than quantum computers, were applied to the problems Standard Chartered is trying to solve that we explored in Part One, they would have a better idea of the narratives and beliefs that actually guide finance and investment.

The consequences of ignoring narratives and relying on quantum machine learning: an amplified repeat of Long Term Capital Management?

In the 1990s, a hedge fund founded by an experienced bond trader, John Meriwether, and with Nobel Prize-winning economists Myron S. Scholes and Robert C. Merton on its board of directors, was launched. That management team included some of the brightest minds in the world.Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) sought to use quantitative models to profit from deviations from fair value in the relationships between liquid securities across nations and asset classes. And it also used a high degree of leverage to do this.Famous investors and economists, including Seth Klarman and Eugene Fama, both believed an inability to accommodate rare events or ‘outliers’, especially in stock prices, was a problem with LTCM’s model. They were concerned, in essence, with uncertainty in a non-stationary problem.

One of the key reasons suggested for LTCM’s collapse was that their models only incorporated five years of financial data. It has been observed that using ten years would have included the 1987 US crash, and eighty years of data would have included Russia’s debt default after the First World War.But would these data actually have helped? We have seen that financial data are non stationary, they are not reproducible and probably do not have stable underlying probability distributions. The assumption that they do is what contributed to the LTCM collapse.Had it been available, would tasking a Born machine with generating synthetic datasets, based even on these longer term samples, have provided an AI machine learning tool with adequate input? Would the patterns it found have been able to cope with the Radical Uncertainty identified by Keynes? Would the approach Standard Chartered is employing, and that we discussed in Part One, have solved the problem?At Rebbelith, we don't think it would. Using using a Born machine in the way Standard Chartered is proposing could amplify the bias in datasets fed to their machine learning tools. We think the intersections of two ‘hypes’ - Quantum Computing and Neural Net AI, could lead to an amplified repeat of something like what befell Long Term Capital Management, on the principle that neither quantum nor neural net processes are directly observable nor easily verifiable.

Final thoughts

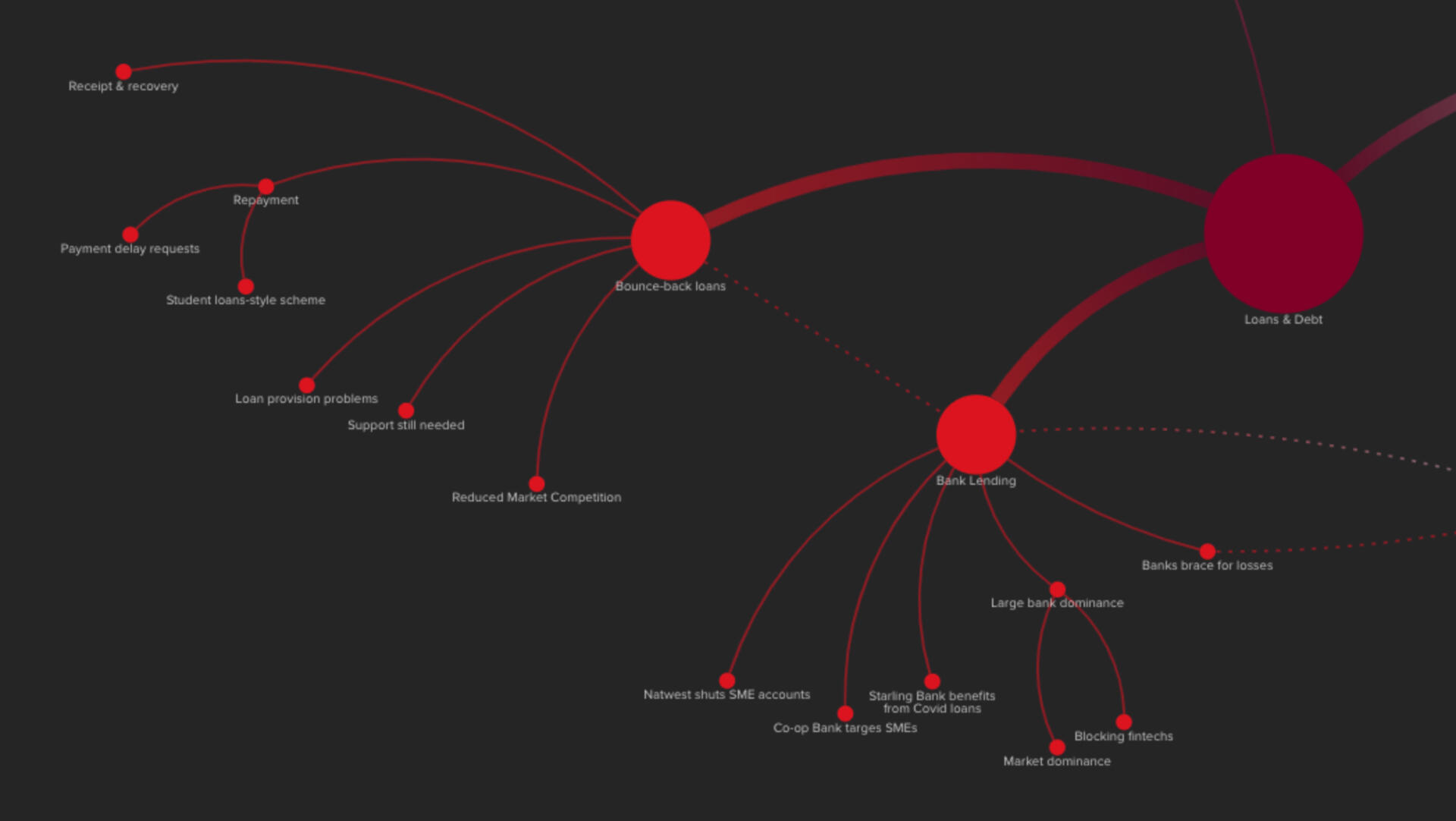

Rebbelith believes narrative networks must be integrated into processes for coping with the kinds of uncertainty faced by business, and those faced by investors - the kinds of uncertainty Keynes spoke of, and that Mervyn King and John kay now write about. What’s exciting is that these narrative networks can now be understood, mapped and navigated in order to do exactly this, addressing many of the points raised by Robert Shiller.We believe that, if they’re used, our brains are capable of performing exactly what's needed to cope with uncertainty in many non-stationary problems like those faced in business - it’s what they have evolved to do.We think that technology and computing power can be used to assist our brains in this task - to help us identify and map narrative networks. Indeed that is exactly what we do at Rebbelith. We do not, however, believe that the ability to cope with such problems will be found in an unobservable AI neural net process, however large a synthetic, biased dataset is used to train it on.

Dominant narratives driving loans and debt - a key factor in SME health in the UK over the last three months.

We wish Standard Chartered well but urge caution. We also noted the similarities between the names of their managing director, who was recently quoted on the project, and the proponent of the Kondratyev wave: if there’s a connection between the two men we’d just ask that, if quantum computing really can eliminate uncertainty in non-stationary problems, he tells us when the business cycle will end so we can make some investment decisions.

About Rebbelith

Rebbelith developed technology to integrate every aspect of campaign and communications strategy into a single service. Our solution uses interactive visual models to help strategists influence complex discussions in the media and map their target stakeholders with new precision.These models are dynamic to accommodate a changing world and help experienced teams navigate uncertainty, giving them a truly competitive edge: not only can they raise awareness of their goals sustainably, but they can now also enter larger media debates more productively, and actually change their structure.Rebbelith achieves this by analysing global news at speed, at scale and internationally. Our systems then explore that media activity to reveal the networks and narratives connecting stories and stakeholders. Finally, these data are converted to condensed visual intelligence, allowing a single strategist to assimilate months of media discussion in minutes, without the need for large research teams.Rebbelith can operate anywhere in the world.

Contact Us

Read Part One

Rebbelith Research

© 2021 Rebbelith Ltd. All rights reserved. UK registered company 12447815